Volume 23 - Spring 2007

Tsbook (Tigrinya for Good) - The Gospel of Abba Garima

by Mark Winstanley

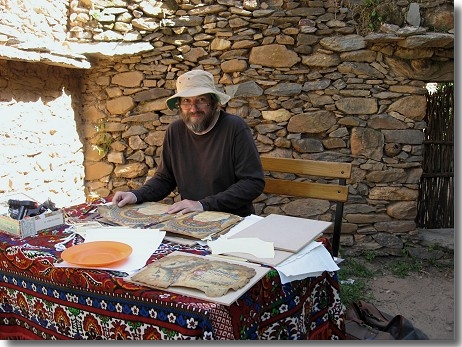

"He is very jumping," said Abba Welda Howareyouat. A black-faced Guereza monkey is interrupting Lester Capon as he repairs a page from Abba Garima's Gospel. A small troop of these long-tailed monkeys daily visit the olive trees that surround the grass compound of the treasury of the Abba Garima Monastery. They are not the only visitors. A troop of baboons forage on the cactus fruit, a grey hornbill calls loudly, a family of Augur's buzzard often throw their shadows over our bindery in the sun. A pair of starlings, but not ordinary starlings, these ones have been caught in paint ball fight, chatter from the lintels of the church. The sky is an impossible deep blue, a cooling breeze threatens to scatter our work and the sun shines warmly here at 8,000 feet in the Tigrean Highlands. Beneath us the landscape is a patchwork of green and golden terraced fields. The rains have been plentiful this year. The shadow that hangs over this rocky, stony but beautiful land is the failure of the rains in the three successive years of 1982, 83 & 84 which lead to the famine.

Who, what, where, when?

Who? - Lester Capon - Bookbinder; Mark Winstanley, assistant to Lester; Jacques Mercier - French scholar of Ethiopian art; Abba Daniel, Ethiopian monk from the Patriarch; Sam Fogg, an English collector.

What? The illuminated pages of the 6th century Gospel of Abba Garima need urgent attention.

Where? At the Abba Garima Monastery near Adwa, Tigray, Northern Ethiopia

When? Early October 2006

Background Details

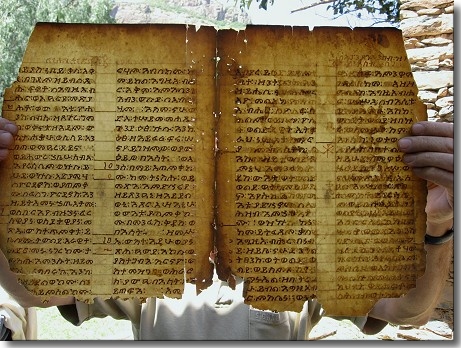

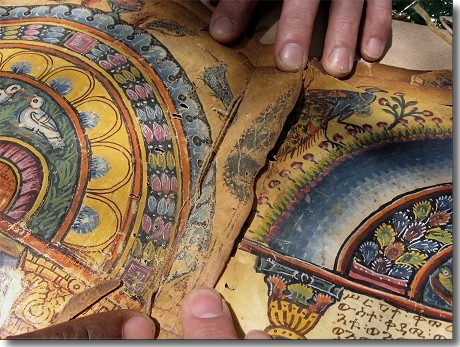

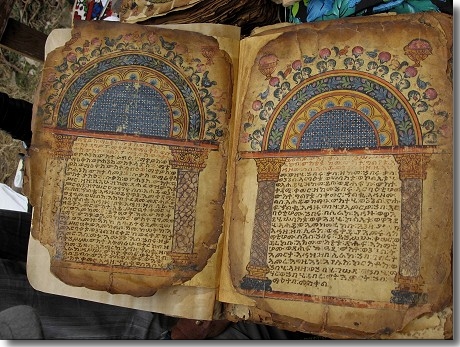

In about 400AD, legend has it that Nine Syrian Saints converted the Abyssians to Christianity. They introduced a much more Judaic version than the Roman, Greek or Coptic, a version that has remained unchanged to this day. The language is Ge'ez and the writing is in Ethiopian script. The Nine Saints also started a monastic movement that has many echoes in Mount Athos. An aversion to the female sex includes cows, mares, nanny goats but not hens. This exclusion still runs and so prevents faranji women from entering the sacred ground of the monasteries. One of the Nine, Abba Garima came to Adua. He founded the monastery where it stands today. Here in Northern Tigray one of the world's most extraordinary miracles has happened. Not that in one day, according to legend, he wrote all 350 pages on sturdy goat's vellum and illuminated the first 12 pages on both volumes. Not that it has survived the destruction of the monastery twice once by Queen Judith, a Falasha queen in the 10th century and second in 1570's by Mohamed Gragn, a Somali Moslem who swept all aside with his Turkish muskets. No, the miracle is that this is the only document of its kind in Africa. There are no known Ethiopian manuscripts older than 11th century. The illuminations are of stunning quality. The artist has used bright colours that retain their lustre. Fiery reds, deep blues and delicate greens suffuse the pages. The black text reveals a clear and confident hand with 23 lines in double columns to the pages. I will mention more about its condition later

I

am not a historian. I was very happy to be Lester Capon's assistant. It was

quite enough to fetch and carry while a real expert worked. As those of you

who work regularly on such sumptuous books, know the constant judgement calls

you must make. This was no different. However there were a few difficulties.

Firstly the bindery was outside. We had to move three times a day to stay out

of the sun. There was no space to store anything apart from two biers (empty

of coffins) on which we dried the dyed Japanese paper and vellum strips. We

were plagued by flies that seemed to take pleasure in exchanging bodily fluids

via our eyes and nostrils. The monks liked to join in. The abbot, Abba Menhr

Tecklamaryat attacked the cord that attached the metal front with a scalpel.

As the atmosphere lightened he borrowed Lester's paring knife to cut his nails,

strewing his cuticles over page 4 of the manuscript. I lent him my 'Leatherman'

as he needed a pedicure. Beside us renovations to a stone hut were in progress.

At one stage a 'chippy' wielding his adze on a doorframe was sending showers

of chippings over our bench. There were constant interruptions. A couple of

donkeys would stroll by and take a few mouthfuls of grass. Ungulate damage wouldn't

have sounded too good in the match report, but the hardest part was Lester's

health. He had a chest infection that was just about kept at bay by pills. How

he managed to complete a long day's work under these conditions is a tribute

to his fortitude and doggedness.

I

am not a historian. I was very happy to be Lester Capon's assistant. It was

quite enough to fetch and carry while a real expert worked. As those of you

who work regularly on such sumptuous books, know the constant judgement calls

you must make. This was no different. However there were a few difficulties.

Firstly the bindery was outside. We had to move three times a day to stay out

of the sun. There was no space to store anything apart from two biers (empty

of coffins) on which we dried the dyed Japanese paper and vellum strips. We

were plagued by flies that seemed to take pleasure in exchanging bodily fluids

via our eyes and nostrils. The monks liked to join in. The abbot, Abba Menhr

Tecklamaryat attacked the cord that attached the metal front with a scalpel.

As the atmosphere lightened he borrowed Lester's paring knife to cut his nails,

strewing his cuticles over page 4 of the manuscript. I lent him my 'Leatherman'

as he needed a pedicure. Beside us renovations to a stone hut were in progress.

At one stage a 'chippy' wielding his adze on a doorframe was sending showers

of chippings over our bench. There were constant interruptions. A couple of

donkeys would stroll by and take a few mouthfuls of grass. Ungulate damage wouldn't

have sounded too good in the match report, but the hardest part was Lester's

health. He had a chest infection that was just about kept at bay by pills. How

he managed to complete a long day's work under these conditions is a tribute

to his fortitude and doggedness.

The Prelude in Adwa

Our journey out did not start particularly well as the loading bay of the Ethiopian Airways jet wouldn't open. We decided to fly on the next flight. At least we had three seats to ourselves so we were well rested as we sat in the hot sun in Addis Abba Airport awaiting a connecting flight to Axon. We board the plane with Jacques Messier and Daniel, a monk from Hayk. We both took the chance to soak up the views of the mountains and green and black chequered fields of rural Tigray. I was only mildly upset to find my luggage, including two small presses, had stayed in Addis (they turn up the following day).

On our way to Adwa in a springless 70's Toyota van we climb over a pass of 9,000 feet. A grand view of extinct volcanoes punctures the horizon. The tiny terraced fields fringed with acacia trees are green with tef and barley. We check into the Tefare Hotel. Its better days were long ago but at least the bed bugs weren't solely to blame for the sleepless nights. They were aided by our first tasting of injera and goat titbits of vindaloo strength, the continual music from the bar, the muezzin's calls to prayer and the chanting from the local church were fairly effective.

We awake to Abba Garima's Saint's Day. We are swept up the hill to the new church by a procession of 5,000. The streets are filled with shamma-shawled pilgrims, the women singing and ululating. In the churchyard ten monks are singing and dancing to the beat of a couple of drums. Their routine may have inspired the Morris dancers. The steps of the church are covered with carpets. In front stand monks crowned with 18th C crowns and helmets shaded by highly coloured umbrellas. Some hold silver and bronze crosses. A metal studded Bible is carried on the shoulder of one monk.

The Pope made his entrance. He is wearing a white beehive bonnet, his robes are a white raiment shot with gold thread. He is flanked by a retinue of black coated, black bearded bishops, who wear black satin caps like judges about to pass the death sentence. The crowd joins in singing with a cantor who after fifteen minutes of plainchant, is cut off in his prime by a papal flunkey. The Pope and his entourage move off slowly downhill followed by the procession of monks with crosses, umbrellas and bibles. We walk down to the marketplace where the crowd forms a hollow square. The Bishop of Mekele makes a rousing speech, the crowd eager for every word. The Pope's homily is, by contrast, greeted with restlessness and general chat. Probably because he congratulated the crowd on their spiritual wealth as opposed to West's material wealth. As we head back to our salubrious hotel the Popemobile, a white Toyota Land cruiser passes. A straggle of boys chase with outstretched hands. A papal palm is tossing out what seems to be Bassett Liquorices Allsorts. In fact they are tiny black Aksumite crosses. With Jacques and Daniel we again eat a challenging meal. Lester has a particularly disgusting concoction of chicken and entrails. He is not well.

The Grist of the Trip

As the Pope is in town the monastery is closed. There is also an issue with the paperwork. Letters from the Patriarch, the Diocese, the Ministry of Culture and Tourism and the EU have to be presented together with the contract to start the repairs on the Bible. Lester and I are blinded by the glow of the 6th C. Eventually we drive up in the afternoon to the hills. Grand scenery unfolds as we climb out of Adwa. The bulbous outcrops of rock look like the dental record of a battered giant who boxed above his weight. Beneath these towering igneous rocks nestle the farms of the peasants. The pre-school children watch over herds of sheep, goats, cows and donkeys.

The Monastery is made up of three churches, a treasury and about fifteen square and circular cells in which the monks live. The ground is very steep. The rough cliffs are covered with cactus and shrubs. The roofs are painted green. The window frames and doors are painted green, red and yellow. Very Bob Marley. Of course it's the other way round. Everything looks well cared for. The entrance to the treasury is a stone portal with steps. Inside this round building a glass cabinet as wide as the room, is filled with crosses, helmets, chalices and manuscripts. From cow horns embedded in the wall, hang leather bible satchels ready for a monk to take on his travels to the outlying villages.

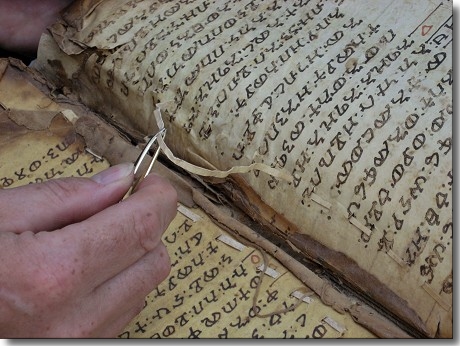

The

talking starts. Jacques and Daniel after three hours persuade the Abbot to let

us see the Garima Gospel - or rather volume 1. A hush and then an awed sigh

falls on Lester and me as we see the metal board opening to reveal the first

6 pages of text. A 2mm wide vellum thong runs through the text about 4mm in

from the gutter. We turn to the illuminated pages. Blues, reds, with birds and

curtained columns lie before us, bright and clear defying the 1600 years between

its creator and us. Another thong is stabbed right through these damaged and

sometimes creased pages, preventing a decent opening. I marvelled at the strength

of the vellum used to survive such a battering. The rest of the book of 300

pages has been gathered into sections of around 8 pages and the Caterpillar

technique has been used. So called, because on removing the strips the holes

left, look like the tracks of a bulldozer. Many of the pages are creased and

damaged but most are in good condition if one overlooks the odd creepy crawly

that emerges from time to time. Although I can't read Ge'ez I found the script

very beautiful. A wonderful strong black line that is clear and flowing. At

this point Lester wants a bit of peace and quiet. A scrum of monks is peering

over his back. It doesn't come out often and this is Abba Garima's own hand.

This is a Sacred Book written by the saint's very own hand. The light starts

to soften. Its time to return to Adwa. Lester has another meal on the wild side.

This time it's a cabbage soup with stale bread. It's disco night at the Tefare.

And the muezzin's sermon starts at 4.30am.

The

talking starts. Jacques and Daniel after three hours persuade the Abbot to let

us see the Garima Gospel - or rather volume 1. A hush and then an awed sigh

falls on Lester and me as we see the metal board opening to reveal the first

6 pages of text. A 2mm wide vellum thong runs through the text about 4mm in

from the gutter. We turn to the illuminated pages. Blues, reds, with birds and

curtained columns lie before us, bright and clear defying the 1600 years between

its creator and us. Another thong is stabbed right through these damaged and

sometimes creased pages, preventing a decent opening. I marvelled at the strength

of the vellum used to survive such a battering. The rest of the book of 300

pages has been gathered into sections of around 8 pages and the Caterpillar

technique has been used. So called, because on removing the strips the holes

left, look like the tracks of a bulldozer. Many of the pages are creased and

damaged but most are in good condition if one overlooks the odd creepy crawly

that emerges from time to time. Although I can't read Ge'ez I found the script

very beautiful. A wonderful strong black line that is clear and flowing. At

this point Lester wants a bit of peace and quiet. A scrum of monks is peering

over his back. It doesn't come out often and this is Abba Garima's own hand.

This is a Sacred Book written by the saint's very own hand. The light starts

to soften. Its time to return to Adwa. Lester has another meal on the wild side.

This time it's a cabbage soup with stale bread. It's disco night at the Tefare.

And the muezzin's sermon starts at 4.30am.

It's Wednesday 12th October and we still have not started work. Before Jacques leaves for Aksum and Addis today, he has three hours to persuade the monks to let us see volume 2, remove the front boards, change the order of the pages in both volumes. He is successful. Lester starts to cut the threads that attach the metal cover. The abbot joins in using a spare scalpel. Lester looks aghast. But there is no stopping our abbot. He helps as the first five pages are de-thonged and even more exciting for him is the releasing of the illuminated pages. However he is very unhappy when we want to number the pages in pencil. So we photograph them. It's going well. Jacques and Daniel leave for Aksum. Now we are on our own. No translator - so we start on a Tigregina course. Tsbook - good; ah'oui - fire; yakanyeahly - thank you; wa'aag - monkey; sir lester - three!

We

start to flatten the pages. Out comes the parchment glue, the Japanese tissue.

The Dryad presses are put into service to nip the repaired edges and to make

up the new sections. As we are the new kids in town there are constant interruptions,

monks, visitors and moving our "bench" out of the hot sun.

We

start to flatten the pages. Out comes the parchment glue, the Japanese tissue.

The Dryad presses are put into service to nip the repaired edges and to make

up the new sections. As we are the new kids in town there are constant interruptions,

monks, visitors and moving our "bench" out of the hot sun.

By 5.30 we are ready for our taxi back to the delights of Adwa. We heard that the Pope decided not to stay in his old monastery but rather at the Holiday Hotel. Civilisation at last. On the cheating side of town in a modern concrete block, clean loos (I'd had to buy Vim at the Tefare) lights that work, but best of all after four days of indigenous nosh we have steak and chips rice and spinach washed with several St George beers. We're happy.

Rather too early Jacques appears to retrieve his computer and then catch a flight to Addis. I'm not happy at missing my breakfast, especially as we have a long day paper repairing. Steady she goes. As the monks become used to us the atmosphere is now relaxed. I find an old pottery beer cup and play the drunk and then do the burning hand trick with Lester's magnifying glass. We rely mostly on sign language which gets us very sweet tea. We wander down to the fields at the end of the day to bird watch. I'm looking out for the family of Augur's buzzard that live in a tall eucalyptus and almost by mistake spot the grey hornbill sand bathing. A flock of green parrots rouse on the branches of a cedar. Weavers and widow birds with their extravagant tails flit from bush to bush. Meanwhile Lester spotted on his hillside walk a family of baboons having a shouting match with the capuchin monkeys. On our return to the Holiday Inn, we receive a worrying call from Jacques that there is a gap in the paperwork. We spend a nervous evening suspecting that the whole endeavour may be curtailed. The prospect of a jobsworth official from the Ministry of Culture & Tourism threatening us with detainment is not the best nightcap. Saturday is market day. We have the compound to ourselves. In spite of the threat from the Ministry, we continue to separate the pages in volume 1. We also manage to move an odd loose illuminated page from vol.2 without any problems. It also gives a chance to examine the book more closely. The book block is in a pretty awful state. Loose pages everywhere in spite of the caterpillar method; for Lester it is a burst mattress. But the silver boards are really special. Of course it is still just about attached to the14th century manuscript, by three very worn threads. The book is about 14 inches thick. The glass case is 8 inches deep; so it stored opened, with a piece of pottery under the board as a support. Nevertheless the vellum is of such durability and strength that it still opens reasonably well. We spend the rest of the day repairing the broken edges, nipping the pages using our makeshift wooden Dryad presses.

Like a bird on a wire

As Sunday is a day of rest and the monks are busy celebrating Mass, we have arranged to take the taxi on a three hour drive to Debre Damo. Unfortunately our early morning start is delayed by a power cut. The petrol pumps didn't work! But by mid morning we are bouncing our way over the dirt road in bright sunlight through the grand scenery of Tigray. Volcanic peaks pepper the skyline. We are in the capital of the terraced field. The tef is just coming into maturity, waving in the breeze like a silken carpet. The wheat fields are being harvested by rows of squatting peasants wielding sickles.

The Chinese are supervising the rebuilding of thousands of culverts and bridges along this mountainous road. We turn off onto a very bumpy road. Occasionally we have to push the Toyota. We drive through a beautiful village built with exquisite stonewalls, reminiscent of the Cotswolds. Now we can see the ambo. We approach on foot.

Arigawa,

one of the Nine Saints, founded this monastery in 4th century. One feels that

he may have been a Stylite with ideas of grandeur. As the ambo has absolutely

vertical sides of at least 80 feet, Arigawa needed the help of a sleepy python

up whose body he climbed. This image is found in many of the bibles, icons and

paintings. Many other church builders in Ethiopia have developed these Alpine

instincts and further a-field the Health and Safety precautions of Debre Demo

are not matched in such a faranji friendly manner. One such church visited by

Pete Marsh has a terrifying approach along a sloping path above a 200 foot drop.

An overhanging chain of 40 feet was left un-ascended. Unlike Arigawa who was

given wings by God when the devil took against him Pete thought a length of

rope and few carabineers might be necessary. It starts to drizzle. We pause

in a talla tavern to eat a snack and to wait for the rain to stop. At the base

a couple of pilgrims have just completed their descent, so I am attached to

the hauling strap. I grab the plaited rope of goatskin. It's almost vertical

and the wall is worn smooth by 1600 years of bare flailing feet, so it's a strenuous

ascent. And after 80 feet I'm pleased to heave myself up over the polished wooden

portal. The monks salaam me and have a good laugh at the faranji. Lester has

quite a struggle. After being landed he has a good breather.

Arigawa,

one of the Nine Saints, founded this monastery in 4th century. One feels that

he may have been a Stylite with ideas of grandeur. As the ambo has absolutely

vertical sides of at least 80 feet, Arigawa needed the help of a sleepy python

up whose body he climbed. This image is found in many of the bibles, icons and

paintings. Many other church builders in Ethiopia have developed these Alpine

instincts and further a-field the Health and Safety precautions of Debre Demo

are not matched in such a faranji friendly manner. One such church visited by

Pete Marsh has a terrifying approach along a sloping path above a 200 foot drop.

An overhanging chain of 40 feet was left un-ascended. Unlike Arigawa who was

given wings by God when the devil took against him Pete thought a length of

rope and few carabineers might be necessary. It starts to drizzle. We pause

in a talla tavern to eat a snack and to wait for the rain to stop. At the base

a couple of pilgrims have just completed their descent, so I am attached to

the hauling strap. I grab the plaited rope of goatskin. It's almost vertical

and the wall is worn smooth by 1600 years of bare flailing feet, so it's a strenuous

ascent. And after 80 feet I'm pleased to heave myself up over the polished wooden

portal. The monks salaam me and have a good laugh at the faranji. Lester has

quite a struggle. After being landed he has a good breather.

Of course the church is a cracker. I'm slightly reminded of Italian Alp chalets. The stonework is so crisp, the wooden ends of the beams protruding through the walls is so unlikely and the marvellous Aksumite biscuit coloured pillar in the entrance is stunning. We walk through the village where the monks have their cells, halls of residence and banqueting. There is wonderful dissymmetry. Large cisterns have been dug in the rock to provide water. We skirt by the sheer sides of the ambo and peer at the tiny caves dug high into the sides of the rock where particularly Garboesque monks withdrew often for years and until death allow another soloist to occupy this tiny room with a view. And all too so we have to leave. Lester is helped by our guide as he is descended down the serpents tail. I rather enjoy the abseil. By the time we reach Adwa, after 3 hours of driving, the taxi is full of peasants happily chatting. Back at the hotel I eat an ambo of lasagne, a truly vast helping.

Monday morning

sees us back in our bibliophile's idyll. However our peace is interrupted as

we make our first acquaintance of Fissela Zibola, the man from the Ministry

of Culture & Tourism.

"Your permit from the Ministry"

"Here's the letter that Jacques left"

"That Jacques has been avoiding me. You have no permit. Stop all work now"

"But the pages are loose"

"You will leave now. I will take back to your hotel."

We

spend the afternoon at a coffee ceremony. The waitresses are cock-a-hoop to

have a faranji or two to entertain. We drink our three cups of spleen bursting

strength coffee amid much laughter and coquetry from the girls. I have time

to hire a Chinese mountain bike. Given the steepness of the hills, it is surprisingly

difficult to find one with brakes.

We

spend the afternoon at a coffee ceremony. The waitresses are cock-a-hoop to

have a faranji or two to entertain. We drink our three cups of spleen bursting

strength coffee amid much laughter and coquetry from the girls. I have time

to hire a Chinese mountain bike. Given the steepness of the hills, it is surprisingly

difficult to find one with brakes.

In spite of my forebodings we are cleared later that evening to return the next day but with an escort from the ministry. We are now under the sharp eye of Moulou, the Ministry representative. His life is typical of so many Tigreans. He has an Eritrean father and Ethiopian mother. In 1984 to escape the famine, their parents carried him and his sisters 300 miles to the Sudanese border. A UN truck took them to a refugee camp in the desert where they stayed for six years. Schools, hospitals and churches were established. On return the war between Eritrea and Ethiopia started. The family was separated. He has not seen or heard from his father since 1999.

We work on toning down the repairs. Soon we are ready to sew the first four sections on vol. 1 and the six sections on vol. 2. It's a two-man job sewing Coptic. Lester has worked out a really neat way of guarding the sections with a vellum strip that allows the pages to turn and open freely. We pass the needle through the section, but require the help of the pliers to draw the needle through. The extra pair of hands is needed to hold the section clear of the book. Lester is very happy at our day's work. We have been lucky that competing parties of patriarch and ministry have let us get on. And my bike ride down the gravel road is glorious. The dodgy brakes enhance the view of the mountains and sunset. A puncture 2kms from the hotel slows me down a bit.

Scenic Interlude

We do have some peaceful days that were flushed by an intense happiness and excitement. The wonderful manuscript of course is pretty inspiring. So are our surroundings. The al fresco bindery, the indigo-blue sky, the monkeys in the trees, the breeze and fluorescent birds are entrancing. We take our lunch, shaded by olive trees on the flat roof of a monk's cell. And the view from Bistro de la Terrace is stupendous. Our diet is sardines with or without sardines on bambasha bread with bananas and oranges. Our digestion is helped by the vista that spreads a thousand feet below. The terraced fields of green tef, the yellow wheat edged by rows of dark green acacia trees form a patchwork of peasant farming unchanged for a millennium. The horizon is pierced by steep, volcanic peaks. The smell of Africa blows over. Dusty, dungy and decidedly addictive. Peasants carrying water drive their flocks of brown sheep, goats and cattle up the stony paths leading their donkeys laden with wood. We stroll up pass the church where the monks are reading the gospel and chanting their song. In the early morning they sit wrapped in their shammas waiting for the warming sun. We salaam and kiss their crosses. Field birds of incandescent colours are chattering in the bushes. Above us a family white-chested Augur's buzzards perch in their cedar tree. Soon the thermals will rise and their shadows will flash across our workbench as they cruise down the valley wheeling and swooping in the soft easterly breeze. An enviable commute.

More binding

We now have three days to complete the work. The pressure is mounting. We need to attach the boards, tone down the guards, trim the vellum guards and reinstate the caterpillar stitch on the vellum linings. And that's just vol.1. Lester and I work away only occasionally interrupted by the monks trying to ride my bike in the compound. Just once do they ride into our bench. A bit of fish wife from me sees them off. Again my ride back is special as I manage to beat the taxi.

Only

two days left now. We attach the gilded bronze boards to vol.1 with a series

of whippings and kettle stitches. By midday vol.2 is progressing well. The fly

leaves of vellum are now dyed down with a mixture of tea and coffee and are

spread-eagled on the bier that serves as our secondly bench. Lester has decided

to reinforce the sewing on vol.2. We repeat the Coptic Twin Method. It was one

of those great moments in my binding life. As we shuttled the needles, all four

of them, through the sections of yellow vellum with their black Ge'ez letters

still legible, still read and still turning after 1,600 years, the touch and

feel of those pages is still with me. I was warmed by the breath of history

on my neck.

Only

two days left now. We attach the gilded bronze boards to vol.1 with a series

of whippings and kettle stitches. By midday vol.2 is progressing well. The fly

leaves of vellum are now dyed down with a mixture of tea and coffee and are

spread-eagled on the bier that serves as our secondly bench. Lester has decided

to reinforce the sewing on vol.2. We repeat the Coptic Twin Method. It was one

of those great moments in my binding life. As we shuttled the needles, all four

of them, through the sections of yellow vellum with their black Ge'ez letters

still legible, still read and still turning after 1,600 years, the touch and

feel of those pages is still with me. I was warmed by the breath of history

on my neck.

What a pleasure, what a thrill and what an honour these humble monks had given us. How lucky we were to have the chance to preserve a part of Abba Garima's Gospel. Now with the folded section and vellum flies fitting sweetly, we thought it looked a picture.

When we met Jacques and Daniel, their tales of intrigue from the Diocese, the Patriarch, the Ministry of Culture sounded tough. But not as tough as the chicken that night. Jacques thanked the waiter for the "food" he had eaten. I promised the Frenchman a "meal" back in England. Or at least a bowl of shiro and injera!

As our last binding day is dawning, we start early. It's Saturday so the people going to market are in full flood. I see a boy carrying four skins of goat looking like very fresh slunk vellum. With him his mother carries on her head a load of wood with a cockerel balanced on the top. I walk down the stony path past the fields emptied of peasants. Only the very young and very old are left to tend the animals. Occasionally the path is lined with flowering aloes. The acacia trees are flushed with their spring growth. In the background there is the hum of a million unseen bees. A hornbill with drunken flight pattern screeches loudly as it spars with our family of buzzards. I reach the valley floor where forty eucalyptus tree trunks lie scattered by the stumps of a once shady grove. By the river in the reed beds are lots of weaver nests. Plenty of them flit about including a red and black one with an 18 inch tail. I turn to meander back up the path. A steer face of volcanic rock looms behind the monastery. The shoulders of the hills are covered with green shrubs with spiky white flowers. A white bell tower, clear against the sky, is perched high on the cliff beside the green round roofs of the monastery. The valley is now filled with the chattering voices of the returning peasants. The married women loaded with wheat, their hair is braided on their foreheads and on their necks is fluffed out in two pom-poms. Often the women attach gold ornaments to their braids. To my salaams they stop, smile, and then firmly shake my hand. Often they slide their shawls off their heads as a sign of respect. The shouts of "faranji" are absent. But my bright shirt and white skin is a sharp reminder of the alieness of my appearance. My face and arms must glow for miles. Just beneath the monastery the peasants stop to bow to and to kiss a large boulder beside the path just as they would the walls of the church.

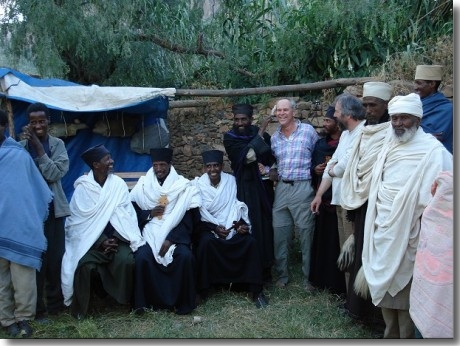

Our work for this trip is finished. The monks have gathered in the treasury. Daniel, Jacques and Momlou are ready with cameras. Lester and I have brought a tea set with 12 glasses as a present for the monks. With Daniel doing the translation we thank the monks. I offer the Abbot Teckla Maryam on bended knee our gift. This causes some consternation and some amazement, as they are not used to a "faranji" bowing before a monk in the position of a supplicant.

Abba

Teckla Maryam stands to say prayers, including the Pater Noster, which I say

in English and they say in Ge'ez. Sorry no recording. They use the joint of

their fingers to count the number of times they repeat the name of Jesus with

their thumbs running along their cupped hands. Just the way my father showed

me the Nepalese shepherds count their animals. The oldest monk, rheumy eyed

with an open sore on his forehead gave thanks, wished us a safe journey and

blessed our families. He said the pictures in the Gospel were of Roma. Did he

mean Constantinople?

Abba

Teckla Maryam stands to say prayers, including the Pater Noster, which I say

in English and they say in Ge'ez. Sorry no recording. They use the joint of

their fingers to count the number of times they repeat the name of Jesus with

their thumbs running along their cupped hands. Just the way my father showed

me the Nepalese shepherds count their animals. The oldest monk, rheumy eyed

with an open sore on his forehead gave thanks, wished us a safe journey and

blessed our families. He said the pictures in the Gospel were of Roma. Did he

mean Constantinople?

During the team photos the mood was lightened by a good deal of horseplay that involved a lot of tickling and arm-twisting. Apparently these affairs are usually a bit serious so it was a real joy to have so many smiling faces.

Back at the hotel a local band is playing. Yamaha organ, lead guitar and vocal. Great stuff. Where are you Andy Kershaw? As it is the evening before the Sabbath, our nearest church is broadcasting not only the service and but also especially the fine voice of its priest. I can hear his alleluias sung a Judaic pre-Gregorian chant. For half an hour this melody, unchanged for sixteen hundred years, washes over my balcony.

Next morning we drive up to the monastery for the last time, with my bike and a sheep on the roof of the taxi. There is a long conversation about the photographing of the finished pages as a letter has emerged from the Patriarch forbidding such activity.

Ever so slightly bored by the chat, Sueravia, a young monk, and I climb up to a spring initiated by Garima's spit. As it still seeps minutely in three places, it is a holy spot where shoes must be removed. We climb higher and I spot a couple mountain goats, grey, horned and extremely fleeting.

On our return we manage to take the shots with only token protest. I wander down to the cliff. In some cactus below I hear the low cough of a monkey. In amongst the spikes I notice a brown animal. At the same time from the undergrowth emerges a male baboon with red nose and a hairy face. He eyeballs me for a second or two, grunts loudly and from the bushes five more bound out and scamper towards the safety of the cliff, exposing their familiar red bottoms. The thought did cross my mind that you don't want to be Lester's apprentice for too long.

I head back to the treasury where a Malmaluk Sultan's tray of 14th C is being shown. One metre across with gold and silver inlays of phoenixes, the Kufic lettering spells out praise for the Sultan. We are about to see their most prized treasure, a 15th C silver chalice with engraving both on the outside and inside when another party arrives. It never appears!

Sadly we say our goodbyes and I mount my bike for the last time and head off into the sunset. The only deflating moment is yet another puncture.

Mark Winstanley - As the son of a Gurkha officer he spent most of his childhood in Malaya. At 8 years old he was sent to Stoke House, a boarding school in Seaford. After five happy years leaning Latin, Fives and playing rugby in the rain he went to Eastbourne College where his only distinction was winning the Fives Cup four years in a row. Luckily his three very mediocre A Levels let him squeeze into the Army. He was commissioned in the Royal Corps of Transport in which he served for four years. The dreary years in Germany were enlivened by a couple of tours to Ulster. He then travelled in the Americas for a couple of years. In 1977 while working in Hay on Wye in one of the many bookshops, he was lucky enough to get a place on Arthur Johnson's Craft Binding course at the London College of Printing. At the end of year show he met John Rose who offered him a job, where he began a belated apprenticeship at Keypoint Francke Bookbinders.

During those 5 years he learnt so much about trade binding and especially about finishing from Bert Knight. He then went to Collis Bird & Withey. Another happy 5 years passed with Nick CB working on the forwarding side.

In 1990 Hannah More, Rosie Gray and Mark decided to start the Wyvern Bindery in Clerkenwell. From a tiny studio they set out to bind in the craft tradition using the best materials making bespoke books. They managed to survive the early years and in 1994 opened a larger bindery on the Clerkenwell Road with a double shop front. After five years of happy partnership, Hannah and Rosie decided that life in the countryside was more appealing than slogging through Hackney. So after a shaky start, he is now the fortunate owner of a bindery that binds all sorts of interesting and beautiful books with an eclectic mix of forwarders and finishers all passionate about the craft. As middle age spreads its greying tentacles he still manage to ski tour, ride, play squash and tennis and take the odd trip to Ethiopia to admire their manuscripts and birds.