Volume 39 - Spring 2015

How to Read Bookbinding Leather

A practical guide - by book conservator, Karen Vidler

Finished Leather at J Hewit & Sons

When choosing leather for a new bookbinding or book repair an understanding of this material can assist in deciding on the best leather for the job. This includes recognising the animal species, how the leather was tanned and dyed and whether the leather was finished with a pigmented and embossed surface finish. These are just some of the processes that influence the final look, workability and durability of leather for bookbinding.

Bookbinding leather making requires a series of physical and chemical processes than can be broken down into three fundamental stages: 1. Removal of unwanted material such as hair, flesh, fat, interfibrillar (within the fibres) materials leaving a network of high protein collagen fibres, softened and interspaced with water 2. Tanning or treating the skin with a tanning agent to displace some of the water and combine with and coat the collagen fibres. Tanning increases the skins resistance to heat, hydrolysis (decay involving water) and microbial attack and 3. Finishing: where the final required thickness and appearance is achieved for the end use of the leather such as bookbinding.

Structure of Animal Skin

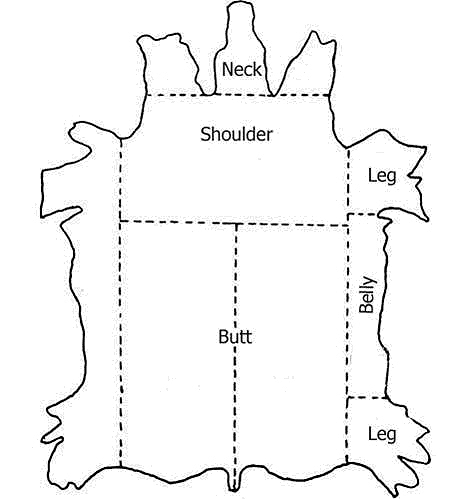

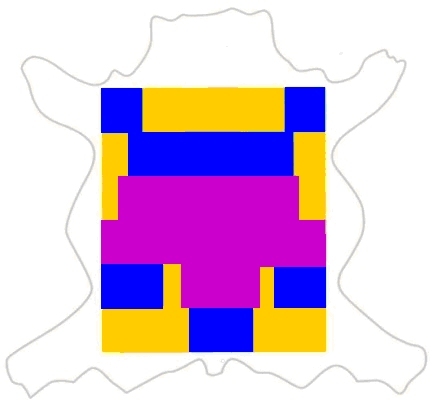

A skin of leather can be divided into different areas to help understand why the leather responds the way it does during the book covering process. Mammalian skins used for bookbinding leather have specific areas that indicate the arrangement of the leather fibres during the life of the animal and the final leather properties. The more elastic areas are where the animal skin stretches such as during movement or increasing weight. This includes the legs, neck and belly regions. The less elastic areas are dimensionally more stable such as the shoulders and butt. In the illustration below these areas are labelled across a mammalian skin. The red areas of the Daniels diagram indicate the optimum selection area for bookbinding and book repair purposes based on measured tensile strength and stretch.

|

|

Labelled diagram of mammalian leather |

R. Daniels contour map of leather performance based on E. Swasyland data |

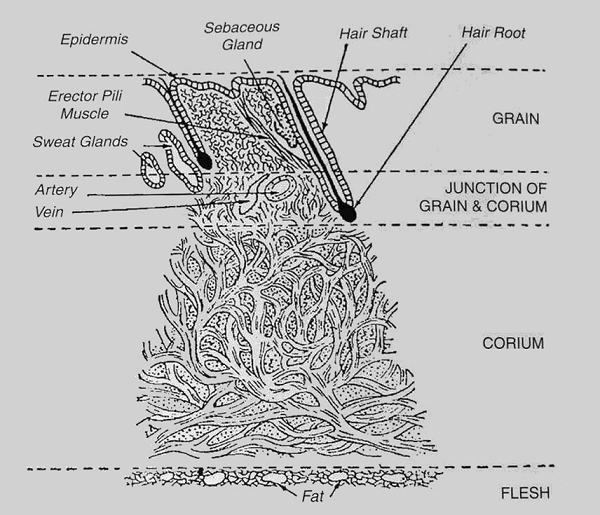

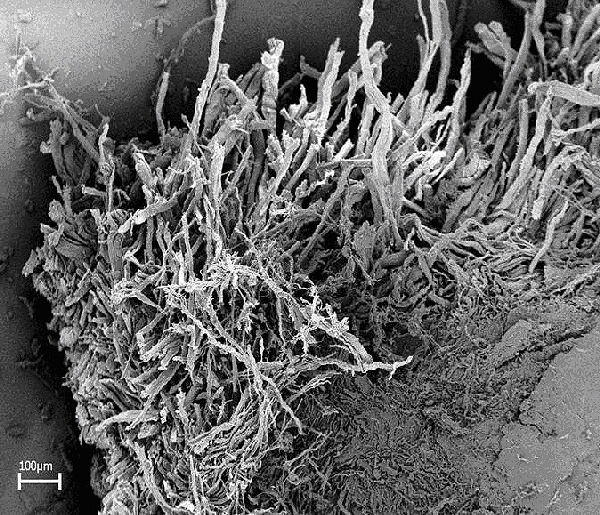

The collagen fibres are arranged into fibre bundles in a woven network running through the thickness of the skin. As can be seen in the well-known cross section diagram by Sharphouse, fibres are arranged into three distinct layers common to all mammals used for bookbinding leather. 1. The upper layer is the all-important grain that the tanner seeks to preserve 2. The central corium layer which is the strongest section of the skin structure 3. The flesh layer of which most is removed during the early stages prior to tanning as this is not required for the final leather. The fibre bundles become more ordered with an increasingly shallow angle of weave as they move from the flesh through the corium to the grain layer of the skin. The hair shafts pass through the skin at varying depths depending on the animal species.

|

|

Leather cross section J.H. Sharphouse Leather Technician's Handbook, 1971 |

SEM image of unravelling calf leather fibres |

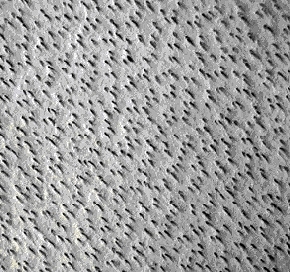

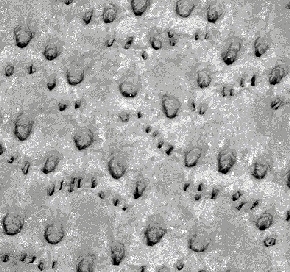

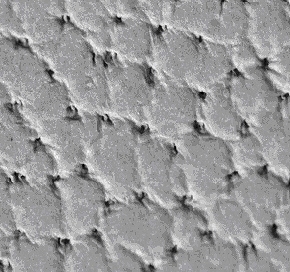

The most commonly used animal species for bookbinding leather include calf, goat, sheep skin and kangaroo and can be ranked for durability. Species recognition can be done following some basic characterisations of each skin and examination with a hand magnifier and lots of practice.

|

|

Calf |

Goat |

|

|

Sheep |

Kangaroo |

Calf skin is characterised by a hair follicle pattern within the skin surface that is evenly sized and spaced along the grain layer with no distinct pathways. The skin has relatively straight and shallow hair shafts that do not interrupt the junction between the grain and corium with uniform fibre bundles through the corium into the grain to impart strength through the leather. But the fibres are arranged at a steep angle so paring will reduce the strength of the final leather at the grain and corium junction.

The grain pattern of goat skin consists of clusters of large guard hairs and small fine hair follicles running in wide pathways across the surface of the skin. The skin structure has an even distribution of fibre bundles throughout the corium and grain and a shallow angle of entry of the guard and fine hair follicles which are evenly spaced throughout the skin. Goat skin leather is considered a durable animal skin for bookbinding purposes because of this strong internal structure.

The grain pattern of hair and wool sheep can be difficult to identify as like goat skin they contain clusters of large guard hairs and small fine hair follicles. Sheep skin is the least durable animal skin for bookbinding leather purposes due to the location of sebaceous (fat) glands that lubricate along the hair shaft being located at the grain and corium junction which leave a 'looseness' to the final leather after tanning. Also sheep skin has been, in recent history, tanned and surface finished with materials and processes that have ensured the leather is less durable over time.

Kangaroo skin has a distinct grain pattern of even sized, fairly straight and narrow hairs arranged in clusters of three or four fine hairs. Clusters run in long pathways across the skin. Internally the fibre bundles are evenly distributed at a low angle of weave with a highly uniform orientation of fibre running almost parallel with the skin causing a high tensile strength between grain and corium. Kangaroo has a thin grain and thick corium layer so paring will not greatly reduce the final strength of the leather. For these reasons Kangaroo is considered to make the most durable leather for bookbinding if tanned and finished correctly.

Tanning Materials

The other main raw material for bookbinding leather making is the vegetable tanning material. A vegetable tannin can be defined as an astringent mixture (quick to bind) of plant polyphenols and non-tannins that chemically bond to the collagen fibres and sourced from barks, leaves, roots and seed pods. The non-tans include sugars, starches, salts and acids that enter the leather, but do not directly react with the collagen fibres. They are thought to be important as they influence the progress of both tanning and the final qualities of the leather such as degree of water resistance, firmness and resistance to atmospheric pollution.

|

|

|

Oak Bark sourced from Great Britain and Europe |

Mimosa sourced from South Africa and Australia |

Sumac source from Africa and Mediterranean |

Traditionally bookbinding leather was tanned with oak bark. With the increased shortage of this raw material in the 18th century new tannins were investigated at a time when the British Empire was exploring the New World. At the same time as the discovery of alternative tanning materials, the discipline of leather chemistry was developing and this led to an understanding of the difference between these agents. Vegetable tannins can be divided into two groups commonly referred to as the condensed and the hydrolysable groups.

The condensed tannins impart a reddish-brown colour to the tanned skin. They are very astringent so penetrate and fix to the collagen fibres quickly so are more popular tanning agents. The red colour is due to the high amount of the phlobaphene compound present in the tannin that reacts quickly to form red products in leather. Condensed tannins are more effective 'sinks' for sulphur dioxide adsorption (on the surface) from acid gas pollution so acid decay is more aggressive. These tannins include Mimosa, Quebracho, Mangrove and Hemlock.

The hydrolysable tannins have been described in the research as the good tans for making more durable bookbinding leather. Usually a yellow-olive or yellow-brown colour is imparted in the tanned skin. This is a less astringent group of tannins so penetration and fixation is generally slower. The tanned leather is thought to contain more carbohydrates or salts (non-tans) which assist in making the skin more resistant to ageing from heat, light and gaseous pollutants. Examples include Sumac, Myrabolans, Chestnut, Valonia and Tara. Oak bark is considered a mix-tan.

Tanning Process

|

Claytons Pit tanning Pit tanning was the common vessel for vegetable tanning groups of skins together prior to the 19th century. These pits were based on the counter-current system whereby skins are put into an old, almost exhausted tanning liquor, then progress through a series of pits of increased strength liquor to fix more tans at a controlled rate. There is very little movement or mechanical action of the skins apart from gentle agitation and the cycle of lifting the skins to inspect and move from one pit to the next. |

Wooden Tanning Drums This system was gradually replaced by the drum tanning method in the mid-18th century or possibly earlier. Modern tanning drums have shelves or spokes that catch the skin during the tanning process which hold it in the air and allow it to drop with some force as the drum turns. This mechanical action squeezes and compresses the skin increasing the rate of penetration of the tannin. |

|

Dyeing the leather

The dyeing of bookbinding leather is also an ancient practice that changes from the use of traditional raw materials to faster acting modern dyestuffs. A dye is a coloured substance that has to have an affinity to the substrate in order to colour that material.

|

Murex Trunculus natural dyestuff Prior to the 1880s the most common dyestuffs were natural dyes of plant and animal extracts. Natural dyes such as logwood (blacks, blues, violets) or brasilwood (browns, reds) were precipitated in water with an inert binder or mordent of metal salts to ensure this affinity with the leather fibres. Most natural dyes were derived from plants sources such as roots, berries, bark, leaves and woods and animals such as the Kermis bettle (pink, red) and Murex Trunculus (Tyrian Purple). These were often found to not be lightfast on ageing and offered a limited colour range. |

Purple dye as developed by William Perkins The development of modern dyes is believed to begin with chemist William Perkins, Manchester, 1856. Perkins first observed a synthetic dye colour from coal tar experiments. This led to the production of mauve and the development of the aniline and azo dye industries that are relied on today for the dyeing of textiles including leather. With the development of lightfast synthetic dyes the dyeing process became simpler and made it possible to drum dye leather almost any shade. |

|

Fatliquoring and Drying

The dyed leather then undergoes the fatliquoring and drying processes. Fatliquoring mostly determines the final mechanical and physical properties of the leather such as it workability. This process separates the leather fibres in the wet state preventing them from sticking together too much during drying - without this leather would be hard and inflexible, as the fibres are not able to pass over each other during flexing. When too little lubricant is applied there is'looseness' between the grain and corium layer. Application of too much lubricant can cause poor adhesion of any surface coatings during finishing.

Hanging leather on toggle frames

Drying is done with the wet skin under tension to set the final arrangement of the leather fibres. Traditional toggling onto a toggle frame is still used by some tanneries or by pasting onto glass sheets and passing through a glass dryer at a controlled temperature and humidity. Pasting on to glass offers a greater final yield in the finished leather. Uneven drying can cause migration of unfixed compounds in the leather up to the surface as well as create loose areas in the skin which are not suitable for bookbinding leather use.

Glass Dryer

Surface Finishes

Generally leather finishing is a group of processes using a mucilage (viscous substance) and mechanical processes to alter the grain layer. This takes place after the drying and softening which requires different manual or mechanical processes to further separate the fibres and increase flexibility of the leather.

Glazing Chieftain Goatskin with glass roller

Traditionally bookbinding leather was seasoned and polished after dyeing. Seasoning mucilage could contain egg albumin, waxes, glycerine, shellac, beeswax, or casein all made soluble in an alkaline solution. This can be slicked on or sprayed applied and polished by hand with a leather covered strop or using a glazing machine.

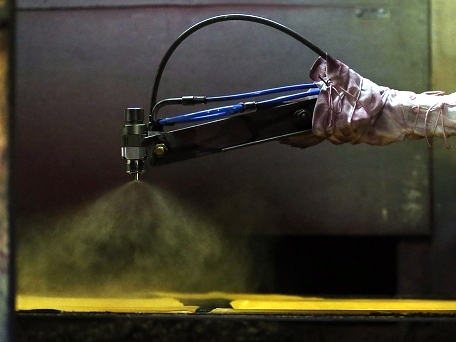

Surface Spraying Bookcalf with Aniline Dye

In the 19th century there were several developments in the leather industry for altering the surface of bookbinding leather instead of dyeing and traditionally surface finishing. These techniques were all intended to improve the natural appearance or reduce defects in the grain layer of leathers or provide an inexpensive imitation of luxury leathers such as Morocco grain for bookbinding purposes. Processes included applying a simple aniline finish layer or coating with a pigment and stamping an embossed pattern.

The aniline finish provides a transparent layer that does not contain any pigment allowing the original grain surface to be seen through the finish. Semi-aniline finished leathers have an application of a small amount of coloured pigment but do not completely conceal the grain. This is intended to disguise minor defects in the

leather.

|

|

Metal embossing plate |

Embossed leather |

A pigmented finish means the grain layer has a surface coating containing particles that leaves the surface opaque. This is often combined with a heat embossed pattern onto the grain surface altering the natural grain appearance. Since the 17th century, plates have been made of wood then metal for leaving an embossed pattern in leather. These are composed of figures in relief that are stamped on to the leather. The effect is transferred by applying a pigmented coating to assist in imprinting the design. Usually the embossed effect on the grain surface is a reproduction of a superior grain such as Morocco goat onto inferior leather that can be sold at a lower price to the binder. Such processes can result in stiffer leather with limited long-term durability.

Conclusion

When selecting leather for bookbinding or repair purposes there are several factors to take into consideration. The leather selected should take account of the required durability of the animal skin, where Kangaroo, when tanned and finished correctly is the most durable, then goat and calf skin. That the vegetable tanning agent impacts on the long term stability of a bookbinding leather. Fortunately, in the UK the bookbinding leather Tanners prefer using the more stable group of tannins, the hydrolysable tans, such as Tara and Sumac for their calf and goat skin leathers. Then whether or not to opt for a dyed leather that retains the natural grain of the animal skin or choose an embossed leather which over time is less durable. But, always remembering when selecting leather for bookbinding the cost of the final leather selected is passed on to the client and the leather must also meet their expectations for cost and aesthetic suitability.

Karen Vidler - is a qualified bookbinder and book conservator, trained at both Guildford College and West Dean College. She has managed a small book conservation practice, Book Conservation Services, since 2006. Her work has included establishing a book and paper conservation studio with the Leather Conservation Centre, Northampton as well as being a Book Conservator with the V&A Museum and The National Archives, Kew. She is a Visiting Tutor on the Books Program, West Dean College, where she teaches the conservation of leather bindings as well as teaching conservation skills to students and qualified Conservators in UK, Europe and more recently Australia. She pursues ongoing research into improving the understanding of bookbinding leather deterioration and treatment.

email: bcsbindery@gmail.com