Volume 39 - Spring 2015

J Hewit & Sons: A Company History

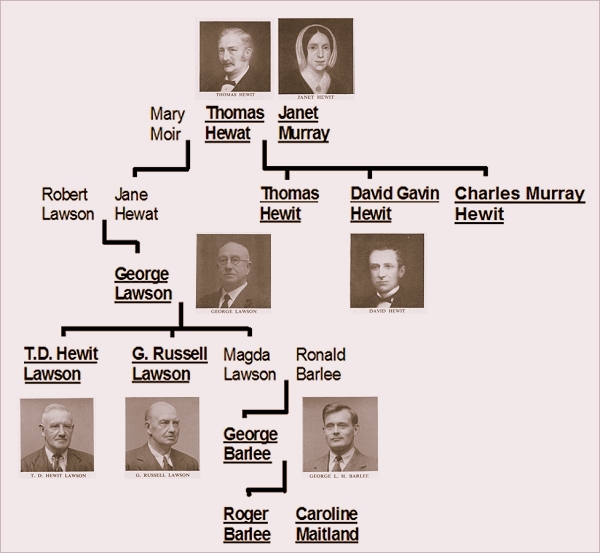

Part 1 - The first 50 years - by Roger Barlee

We were recently contacted by Family Business United who have done research into the oldest family run businesses in Scotland. To my surprise we came in as the third oldest private family firm still in existence. As you will see later on in this article the 31st of December 2014 was an important day in the history of J. Hewit & Sons Ltd, and having discovered some inaccuracies in our historical information, this prompted me to start writing down the history of the Company. Over the next few editions I intend to elaborate on the history of the Company.

J. Hewit & Sons Ltd can trace their history in the leather trade back to 1814, however the business of Thomas Hewat/Hewit Leather merchant did not start until 1822. Thomas was the younger son of Thomas Hewat and Sarah Gavin, Thomas (senior) being a writer, which I believe meant that he was probably a clerk in a lawyer's practice.

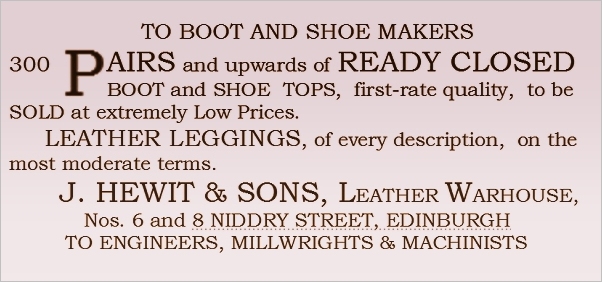

Our Thomas was born around 1800 in Edinburgh. Thomas' father died when he was young and in 1814 he was apprenticed to John Moir, a shoemaker in Candlemaker Row, famous to many as the statue of Greyfriars Bobby is situated at the top of the street. After his apprenticeship Thomas qualified as a shoemaker and in 1822 married Mary Moir, the daughter of John, setting himself up as a leather merchant at 29 Niddry Street, in the heart of Edinburgh's leather district, off the Royal Mile. The "Boot and Shoe" department as it was called in later years ran until the late 1960's servicing the independent shoemakers of Edinburgh.

Thomas and Mary had two children including Jane, my great great grandmother. Tragedy struck the family in 1828 when Mary died in childbirth, however a year later Thomas married his wife's cousin Janet Murray. Over the next few years Thomas and Janet had three sons of their own, Thomas, David Gavin and Charles Murray.

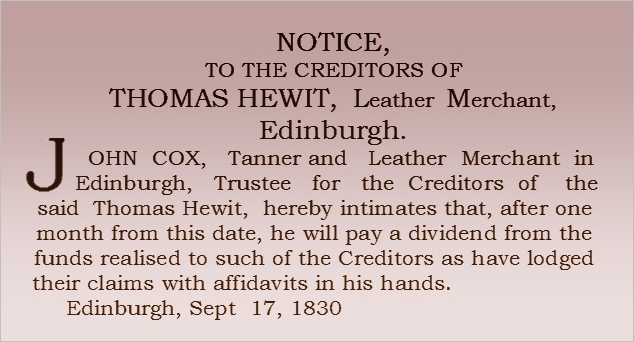

I am unsure of the causes, but in 1830 there was an article published in "The Scotsman" that indicates that Thomas had gone bankrupt.

The business however appears to have continued trading and must have received funding from somewhere, possibly from Thomas' father in law, as within 3 years the family was living in Surgeon Square, one of the more prestigious addresses in Old Edinburgh.

From the street directories it is evident that the company had also begun Currying (dyeing and oiling) their own leather. The listing in the 1834 Edinburgh postal directory states "Hewat Tho. Currier and Leather Mercht.". Currying is an old term that is barely heard of these days. An act of Parliament around 1600 made it illegal for the process of tanning leather and the subsequent currying of skins to be done on the same premises. This state of affairs lasted until around 1820 when this act was repealed.

Surgeons SquareTo understand the role performed by the currier, it is necessary to look at the earlier stages in the leather-making process. The animal skins were delivered to a tannery and there they were soaked and cleaned before liming, the process that opened up the fibres and facilitated the removal of the hair. After being cut to a suitable size, the skin was placed in successive tanks of progressively stronger tanning solution. The solution used for tanning was traditionally made from oak bark.

After careful drying the unfinished leather then passed to the currier, whose craft was to transform the stiff material into a pliant, workable material for the final craftsman to transform into the finished product. Just as tanners were prevented from being curriers until the 1820s, curriers were also forbidden to be leatherworkers. After this date however curriers were often shoemakers, so this would have been a logical move by Thomas, giving him better control of the products he was selling.

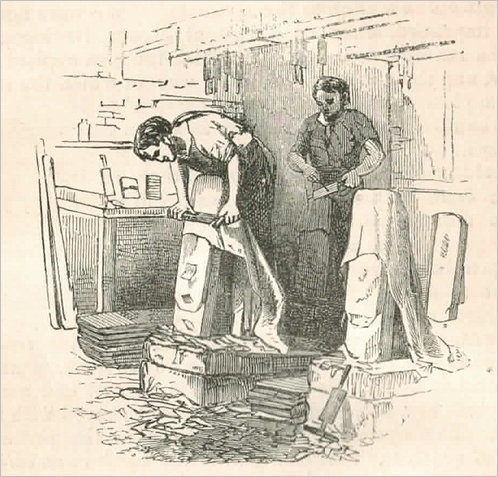

The art of currying leather involved hard manual labour, needing great skill and a range of special hand tools. The hide was first trimmed to a suitable size and shaved to substance by hand.

|

|

Hand Shaving |

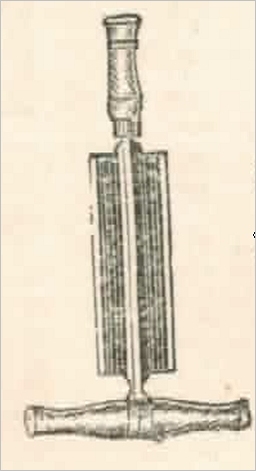

Shaving Knife |

After this the hide was stretched on a frame and the currier would gradually tighten the frame in every direction until satisfied that the hide was as taut as possible. Once stretched, the tanned leather was washed and scrubbed. This part of the process was demanding physical labour which softened the skin. The currier then went to work with a "slicker", a short bladed blunt knife. The sleeker forced the remaining unfixed tanning fluid from the hide. The skin was then ready to be dressed.

A currying shop including the use of slickers on the tables

We still use slickers here today, both for squeezing water out of skins on our plate glass drying machine and when softening calfskins cracking. Once curried, leather could be used for a wider range of purposes, and also stained or dyed.

Scouring large seal skins by hand using slickers

Having finally prepared the skins the currier carried out the process of currying. That is, massaging the leather using beef tallow, neatsfoot oil or cod liver oil. This had the effect of softening the skins and preventing the leather from cracking. Once curried, leather could be used for a wider range of purposes and also stained or dyed.

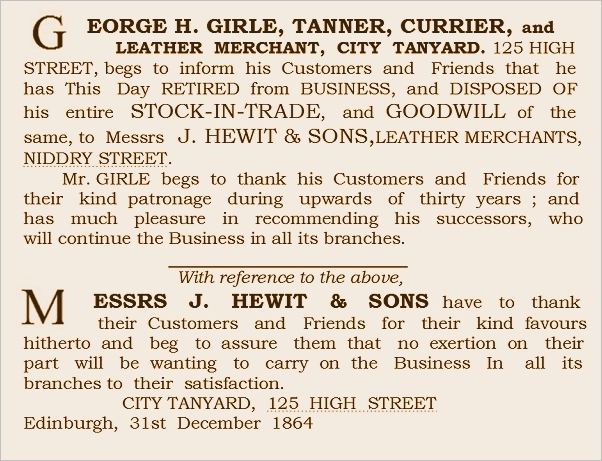

Thomas almost certainly obtained most if not all his skins from the City Tanworks, 125 High Street, run by George Girle as this tannery was only 100 yards from his premises.

Thomas suffered poor health, and temporarily closed his business during 1844 before reopening. After a prolonged period of illness Thomas died on the 30th December 1846 leaving his wife, Janet, and the three boys aged 16,10 and 4. The business then continued initially under the name Thomas Hewit jnr, then Mrs T Hewit, and finally in 1854 J. Hewit & Sons.

Running any business in the mid 1800's was quite an achievement for a lady, particularly a heavy industrial process like currying. Janet was obviously a very strong-willed lady and showed this when a year before Thomas' death she had persuaded him to change his will to leave nothing to the children from his first marriage. The lawyer noted on the will that Thomas was so weak at the time that he had to rest in the middle of signing his name. Thomas did recover sufficiently to add a codicil to leave some assets to his first two children.

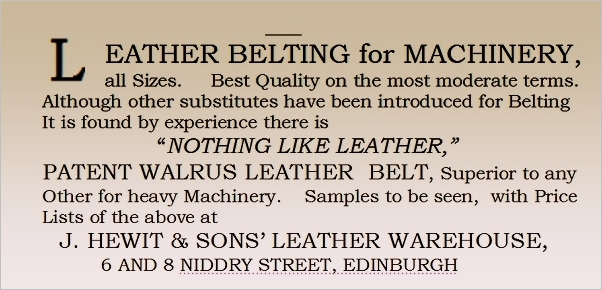

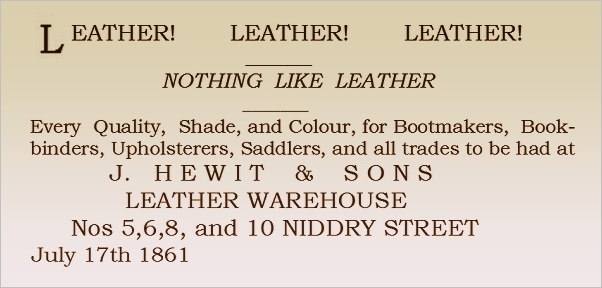

The company obviously thrived over the next twenty years, and adverts in 'The Scotsman' in the early 1860's give some ideas of the many different areas they became involved with during this period. Interestingly the third advert shows that we were already dealing with bookbinders as early as 1861.

When Mr Girle decided to retire in 1864, taking over the tannery was the next obvious stage allowing the expansion into the tanning of their own leather. The following article was published in 'The Scotsman' on several days around the year-end. The 31st of December 2014 was therefore the 150th anniversary of J. Hewit & Sons starting to tan leather.

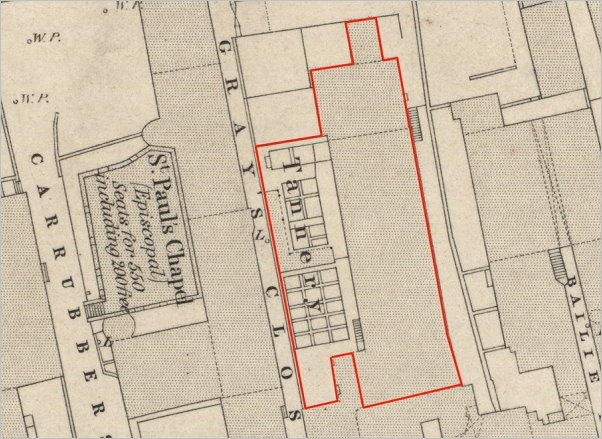

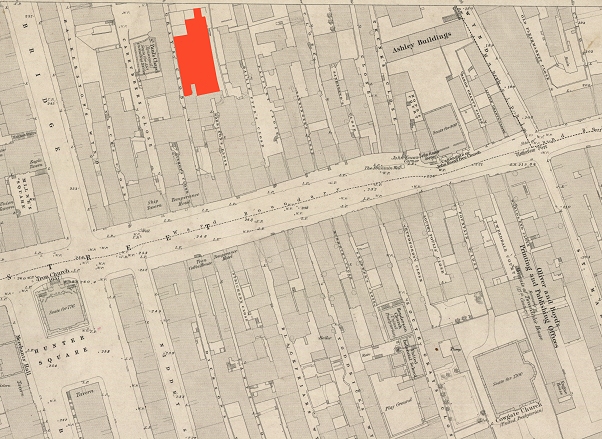

The map below was published in 1852 and shows the City Tanworks in its original form. The tannery consisted of liming and tanning pits along with some yardage for storing chemicals, oak bark and skins. The tannery was very much cheek-by-jowl with the local tenement blocks down North Grays close, barely 4 feet at its widest and only a couple of hundred yards from John Knox's house on Edinburgh's Royal Mile.

City Tan Works 1852 - OS Edinburgh 1852

(sheet 36 by permission of National Library of Scotland)

The site of our first tannery is now bare land, and the area was recently excavated. I was allowed access to the site along with my father, and these original tanning and liming pits were still very much in evidence.